|

By Abdus Sattar Ghazali

Sixty Nine years ago one of the greatest and most violent upheavals of the 20th century took place on the Indian subcontinent. In August 1947 the sub-continent was partitioned into India and Pakistan as the British pursued a “divide and conquer” strategy. The partition involved the movement of some 12 million people, uprooted, ordered out, or fleeing their homes and seeking safety. Hundreds of thousands of people were killed, thousands of children disappeared and thousands of women were raped or abducted. The violence polarized communities on the subcontinent as never before. Across the Indian subcontinent, communities that had coexisted for almost a millennium attacked each other in a terrifying outbreak of sectarian violence and an unprecedented mutual genocide. Tellingly, one of the worst ethnic manslaughters on the face of the earth has unfortunately not received the emphasis it deserves in the annals of historic literature.

Historians have so far mainly focused on the causes of partition and endlessly debated whether it was inevitable and who was responsible for it. However, in recent years some writers from India and Pakistan have taken initiative to record this communal holocaust. In August 2010, Berkeley-based Dr. Guneeta Singh Bhalla launched 'The 1947 Partition Archive' project to record the dislocation of human lives and the loss, trauma, pain and violence people suffered. In Pakistan Anam Zakaria, author of 'The Footprints Of Partition: Narratives Of Four Generations Of Pakistanis And Indians', runs the Oral History Project, collecting Partition narratives of first and second generation Pakistanis.

In the same spirit, Dr. Priya Satia, Associate Professor of History at Stanford University, ventured to capture the history of partition through poetry. Dr. Satia, the prize-winning author of Spies in Arabia: The Great War and the Cultural Foundations of Britain’s Covert Empire in the Middle East, presented a her well researched paper "Poets of Partition", at the July 17, 2016 literary event of the Urdu Academy of North America. The event, held at the Chandni Restaurant, Fremont/Newark CA, was attended by more than 100 Urdu lovers. Scores of guests came from the Indian Community Center, Milpitas CA. Dr. Khwaja Muhammad Zakaria presided over the event.

Dr. Priya Satia explored the experience and thoughts of Urdu poets who lived through the Partition of India in 1947. The story of Partition is typically told through the lens of high politics, Dr. Satia presented the alternative political visions of an influential set of cultural actors.

Through their lives and poetry we can excavate what other visions of the subcontinent's future were on the table from the 1920s to 1950s, says Dr. Satia.

Her talk ranged over the lives and work of many poets, but key figures include Faiz Ahmed Faiz, Makhdoom, Hasrat Mohani, Mohammad Ali Jauhar, Allama Iqbal, Jagan Naath Azad and Amrita Pritam.

Dr. Satia also invoked earlier names like Ghalib and Daagh as well. The talk also explored what, if anything, the poet's lost causes can tell us about future possibilities.

Dr. Satia argues that poetry seems an obvious recourse to expressing the loss and grief experienced by those affected by the redrawing of international borders, as it was in Bengal, Germany, Palestine, Ireland, and elsewhere; in Punjabi and Urdu poetry, partition already existed as a theme, through mystical traditions and earlier emigrations.

A number of Urdu enthusiasts recited poetry of the poets mentioned in Dr. Satia’s paper”: Arvind Kumar, Moiz Khan, Javaid Umerani, Hatem Rani, Tassaduq Hussain Attari, Khalid Rana, Khalid Iqbal, Falak Singh, Kausar Sayed and Tashie Zaheer.

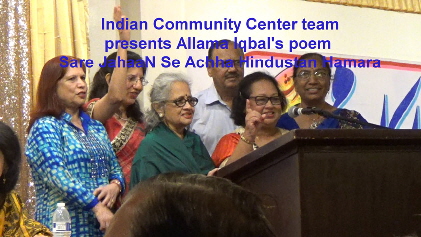

The salient feature of the program was a chorus by the Indian Community Center, Milpitas volunteers who thrilled the audience with the popular poem of Allama Mohammad Iqbal, Sare JahaN Se Achha HindustaN Hamara.

Here are excerpts from Professor Satia’s paper on Poets of Partition:

“My attempt at excavating Urdu poets’ lost causes here is far from exhaustive; I will leave out major writers and thinkers, I will fail to distinguish between “Urdu” and “Punjabi,” I will wax personal in places. Indeed, I focus entirely on Punjab without scruple although an enormous Bengali story runs parallel to and intersects with it, which I have neither the space nor skill to address. But still the exercise of recovery, however uneven and admittedly self-indulgent, is useful precisely insofar as it raises the possibility of countless alternatives, on which more at the end of this essay.”

“The 1940s, 1960s, 1980s, 2000s produced countless stories of displacement among Punjabis, not to mention those who left even earlier, during colonial times, in the service of the British Indian Army or to escape British rule and poverty by becoming farmers in North America, especially California,” Dr. Satia said adding: Heavy military recruitment from the second half of the nineteenth century and emigration to North American farmlands from the early twentieth century fuelled the poetic tradition around the pardesi and the cult of nostalgia for a homeland that the British transformed into a “resource for supporting a security regime in northwest India.”

“Displacement became central to Punjabi identity as it is to Jewish and Armenian identity, but it is distinct in the Punjabi’s awareness of his own role in his tragic severance from his home and repeated division of his homeland. His (and I do mean “his” here) is a self-imposed exile guiltily justified by one or another promise of modernity—personal prosperity, for economic migrants; national prosperity for partition refugees. He self-consciously martyrs the homeland for the progress of its children, secure that in dutifully pursuing his worldly ends he nevertheless maintains a timeless bond with it, a bond made more transcendently spiritual at each remove from the geopolitical reality of a place called Punjab.

“Bollywood films packaging our stereotypical Punjabi-who-transcends-Punjab also play on that gendered Sufi idiom: the centuries-old poetic romances of sundered yet mystically united pairs: Heer-Ranjha, Sohni-Mahiwal, Sassi-Punnu, Mirza-Sahiba. There are others — Shirin Farhad, Laila Majnun — inherited from further northwest. The most famous narration of Heer Ranjha is Waris Shah’s from 1766, based on a true story that transpired some two centuries earlier in Jhang. The tragic ending depicting the two lovers, dead before the chance at union, at once sought to express divine love, in which the most intense experience of union with the divine lies in interminable longing. Is it coincidence or destiny that a region that for so long depicted love through partition should have been the site of violent partition itself? Or is the intense Punjabi preoccupation with these romances a cultural legacy of 1947?

“The Punjabi poet Amrita Pritam, who left Lahore in 1947, explicitly invoked this cultural coincidence to express her anguish over Partition, particularly the violence done to women, in her much loved poem “Ajj Aakhaan Waris Shah Nu” (“Ode to Waris Shah”). Her sentiments and those gestating in the film industry were connected; many of the poets of the world I want to describe were part of the Progressive Writers’ Association (PWA), which was closely tied to the Indian People’s Theatre Association; and actors and writers in these groups were tied to Bombay’s film industry; indeed, Partition brought an influx of displaced artistic people there (some migrating to Pakistan but then returning to India), including the object of Pritam’s love, Sahir Ludhianvi, as well as Majrooh Sultanpuri, Ismat Chugtai, Bhisham Sahni, Sajjad Zaheer, and others. After a detour through this artistic universe, I will return to the plight of Heer that Pritam invoked.”

Read full article

See More Pictures

Watch videos on You Tube

|